It was a random phone call: “How many of your classes will I need to attend before I can save at least 50% — maybe 100%– on my food bill?” The caller primarily wanted to save money on his food bills using wild foods.

How long does it take to learn about the wild plant of the world, and their medicinal and edible properties? It takes time, and like any science or art, the time it takes you depends upon how much time and effort you’re willing to devote to the study and practice.

At an early age, I became interested in knowing exactly how native Americans of past days could live off the land when there were no supermarkets, hospitals, or hardware stores. My sources of information were my botany and science teachers, living Native Americans, the library at the Southwest Museum, and anyone who would listen to my questions. I spent a considerable amount of time in the beginning learning mycology, and going into the field with experts to learn how to recognize wild mushrooms, and learn about their growing conditions. Along the way, you cannot help but learn about the trees and plants and environments which produce the mushrooms.

Students learning how to identify wild plants.

I had probably spent at least five years of fairly actively research and study of wild plants and their uses before I spent my first period time trying to subsist entirely on wild plants. Though there was still a lot that I didn’t know, I was able to eat well for a week at a time because there was an abundance of the plants that I did know.

Though I continue to study and learn about the uses of wild plants, I have never had the goal of trying to live exclusively from wild plants, except for short periods of time. The reasons for this are many, but for example, I love to garden and produce food, and I have raised chickens for their eggs many times over the years. I am a strong advocate of supporting your local farms, since in most areas, the wild foods alone today would not support the population. There are also some foods that I really like which I cannot get in the wild, such as ice cream and potato chips. (Yes, I admit that I enjoy those).

So, getting back to the random phone call…

I had a short discussion with the man. First, had he ever eaten any wild foods – in other woods, did he know what they would taste like and how they might fit into his and his family’s existing diet? The answer: No.

Then, had he ever identified any edible wild plants? In other words, had he ever done any training necessarily in order to safely recognize a wild plant that he could actually eat. The Answer: No.

Ryan closely examines the Nettle plant.

I told him a little about my path, how I never pursued the study of ethno-botany from the standpoint of saving money, but rather from the perspective of “survival.” Plus, the more I studied, the more I learned that some of the most nutritious foods today are wild foods, far superior to many, if not most, farm-grown foods. He listened politely and the re-iterated his question: How many classes would he have to take from me before he could cut his food bill 50%, and then, 100%?

I explained that he was asking the wrong questions, and thinking about it all wrong. One obvious point is that – especially in urban areas – there are not enough wild areas, and wild foods, to support even one family who used exclusively wild foods. But since saving money was this man’s primary focus – a man who had never studied botany – I began to list for him all the ways he could cut his family’s food bill. I suggested buying at co-ops, and the ubiquitous dollar stores. I suggested he do as I have done, and clip coupons from the newspaper to get discounts. I suggested he buy in bulk. I suggested that he and his family begin by growing at least some of their food, so they can learn about plants and the harvesting of plants. I suggested some of the very easiest garden plants that any amateur could easily grow and produce food: radishes, potatoes, onions, chard and other greens, and even appropriate fruit trees. I also suggested that he and his family members consider getting extra work to pay the expenses, and even getting federal food stamps, if they qualify.

He listened politely, said thank you, and I never heard from him again. I had let him know that the knowledge of wild foods, and the practical daily use of wild plants, could definitely improve the quality of his life and the quality of his diet. I also pointed out that because of the time it takes to learn each new plant, the saving of a significant amount of money on his food bill in the short term should not be the reason why he pursues the study. I have no idea what action the man eventually took but I know that his idea of saving money is not unique. I have heard it in various forms over the years. My advice is always the same: Learning about local plants and their uses is an excellent long-term self-reliance and survival strategy. You will continue to reap benefits as you continue to study and practice these skills. You might even feed yourself in an emergency when no other food is available.

Rick and Angel work on the wild food meal.

Saving money is always a good thing, but it should not be your primary motivation to pursue the study of ethnobotany in general, and wild foods in particular.

SO, HOW DO YOU LEARN ABOUT WILD FOODS?

John studies the unique wild radish pods.

Though interest in foraging has grown greatly in the last decade, it is a skill and art that goes back to our hunter-gatherer roots in ancient Africa, a skill that the family of mankind took with them wherever they went. Today, fortunately for the modern person with solid roots in the city, there are some very well-trodden paths that you can follow to learn about the uses of plants.

1. Enroll in a class local to you where you can see the plants in person.

Depending on your particular specific interest, you will be pursuing some aspect of botany. Botany is a science, so along the way, you will learn some of the specific language to this science. But if you enroll in a class in just “Botany,” you might be disappointed. Though botany is a foundation for ethnobotany and all the other related disciplines, botany per se is the study of the classification of plants, how they grow, their cellular structure, etc. The uses of plants tend to be a footnote to Botany classes.

The uses of plants might be classified as Ethnobotany, or cultural botany, or anthropological botany, or some other title. If you want to know about the medicinal uses of plants, you’re going to be a student of Herbalism.

2. Join some of the excellent on-line groups where wild plants are discussed and identified.

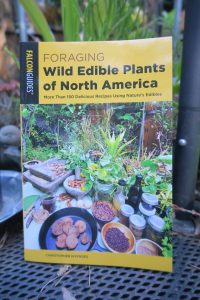

3. Buy one of my many books on wild foods – for starters, “Guide to Wild Foods and Useful Plants,” and “Foraging Wild Edible Plants of North America.

4. For the botanical aspects, buy “Botany in a Day” by Tom Elpel.

[A listing of the Classes by Nyerges and staff can be seen at www.SchoolofSelf-Reliance.com. You can also request a schedule be sent to you by writing to School of Self-Reliance, Box 41834, Eagle Rock, CA 90041]

Nyerges book, “Foraging Wild Edible Plants of North America”

#Cover Photo: Students working together to shell, grind, and leach acorns to make acorn pancakes.