One Man’s Quest to Make Fire

How Adam Nestor made fire for the first time

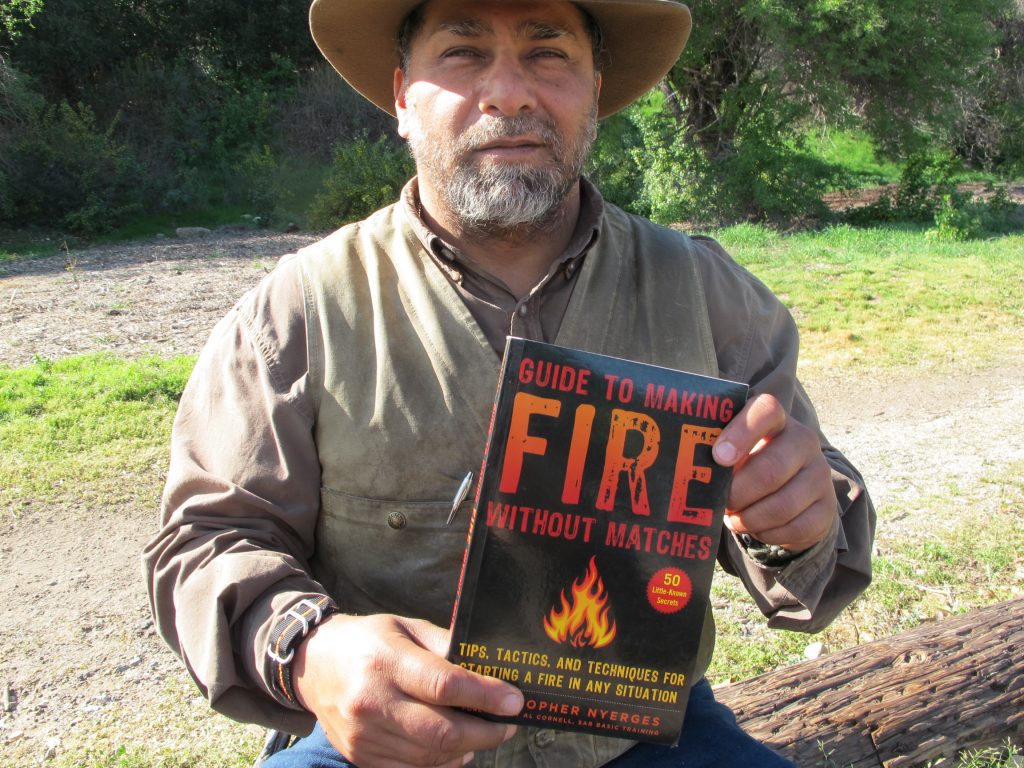

Christopher Nyerges [www.SchoolofSelf-Reliance.com]

One of the classes I conduct regularly is called the Survival Skills Intensive, where students learn a little bit about everything: wild foods, cooking, making fire primitively, shelters, water purification, traps, making rope from yucca, and more.

When Adam Nestor was a Marine, stationed at Camp Pendleton, he drove north from his base nearly 200 miles to attend one of my all day Survival Skills Intensives in the Angeles National Forest.

Though it wasn’t rare that someone would drive this far to take one of my classes, I originally found it unusual that a Marine would travel that far. After all, I asked one Marine friend, aren’t you learning all this with your regular training? No, I was told, Marines are generally not taught outdoor survival skills as a part of their overall training. There are other skills that are regarded as more relevant to military training, such as working with your team, logistics, knowing your weapon, and so forth.

Nestor had already taken a few classes from me and so I recognized him when he arrived. He told me that he knew the agenda for the day, but asked me if I could guide him through making a fire with a bow and drill, with only materials he found that day. Sure, I told him. As we walked along the two miles to our destination, I made a point of looking for the raw materials that Nestor could use to make fire.

We needed to find the raw materials for the hearth, the drill, the bow, the bow-cord, and the bearing block. Though I had taught this skill hundreds of times, it was not usual for me to collect all the materials on the day of the class. In fact, I was not 100% sure that we would find everything we needed, though I told Nestor I’d make a good effort.

Keep in mind that as our class walked along, and I talked about the edible and medicinal uses of plants, and how to detect where animals had been, I had to “fit-in” the need to find each piece that Nestor would need to make his fire.

We walked along a stream where alder trees were common, and so I found a slim alder branch, slightly thinner than my thumb, and cut the branch at about two feet long. This would be the bow.

Further along, we encountered a patch of mulefat, which is a member of the sunflower family with long straight stems, generally no thicker than one’s little finger. These were widely used by Native peoples in the past for building their half-domed shelters, and for arrow and spear shafts, as well as fire drills. Generally, if you want the best drill, you cut the wood green and let it dry. But because of the need to make a fire that day with what we could find, we searched around in the mulefat patch until we found a dead piece. We cut a few about 18 inches long. That’s a bit longer than needed for a bow-drill, but we figured we could always trim it down when we were ready to make the fire.

Since we were on a heavily-traveled trail, there were odd bits of trash scattered about. Twice I found discarded nylon rope that would have been ideal for the bow-string, and offered it to Nestor. Nestor had wanted to use a natural yucca-leaf bowstring, but at that time his skill at twining was not sufficient to make that work. So he accepted the man-made cordage I’d found on the trail so he could make his first fire from the bow drill that day. (That was a long time ago– currently, Nestor has made over 1,000 fires made with natural cordage.)

I was still on the lookout for a hearth and a bearing block, and we found both in a massive pile of driftwood that had collected on the river from the last storm. We found a burl of hard wood – probably oak – which we were able to cut down so that it would fit the hand. It had a small naturally-occurring hollow where the drill would stay while being pressed down. We also found a three foot length of dried alder branch, about four inches in diameter. We sawed each end of the alder branch so there was a clean cut, and then we stood it up, and split it in half with a big knife. Each of the two halves of the log was then further reduced, which produced two hearths, each about 3 ½ inches wide by about 12 inches long.

At this point, Nestor had everything he needed to make his first fire with materials he’d collected that day.

It was another hour or so before we got into our camp where we could make fire. Along the way, we worked on building a lean-to, purified some water, and collected various wild plants for our lunch.

When we made it into our camp, and I got everyone busy making our cook fire and teaching how to make a net, Nestor worked off to the side preparing his materials. The hearth and bearing block were ready to go. He trimmed the drill down to about a foot long, and he sharpened each edge. Next, he tied his twine onto his alder bow. Though the bow had a little flex, he still had to tie the cord tight enough so it would not slip.

Nestor prepared his hearth with a little gouge, and a triangular cut to the edge where the dust would flow. Now he was ready to go. He got into position, and slowly began to spin his mulefat drill with the bow, and the drill immediately popped out. That’s normal, and so he put the drill back on the cord, and began once more. His body position was good, and he was applying sufficient pressure and after a few minutes, the drill would pop out. Making fire with the bow and drill is a constant series of minor corrections. Nestor continued, determined to get an ember, and carefully began his drilling. Patiently, he drilled consistently back and forth, and smoke flowed from the contact between the drill and hearth, and quickly increased. I carefully watched Nestor at this point, and encouraged him to not stop. He increased his speed and pressure just slightly, and as he was drilling quickly, the drill popped out again, and Nestor seemed dejected.

“Hold on,” I yelled. “Be careful, you got an ember.” In his pile of accumulated dust, a red ember had formed and Nestor had succeeded in step one of getting a fire with the bow and drill. He carefully put the ember into a birdnest of dried mugwort leaves, and gently and carefully blew the ember larger and larger. Then Nestor put this birdnest, now smoking heartily, into a larger birdnest of dried grass, and you could see the smile on his face as he kept blowing and the embers grew.

By now, everyone else in the small class was fixating on Nestor’s challenge, and when his bundle of dried grasses burst into flame, everyone applauded as Nestor beamed.

Not everyone recognized the accomplishment that Nestor had achieved that day because they had only observed, and not actually done it. Nestor had achieved a goal that he set for himself, and thereby rose from the ranks of just talking about something, to the makings of a true fire-master.

The steps that Nestor followed that day to achieve his goal is precisely how anyone can achieve whatever goal they set for themselves.