By Christopher Nyerges

[Nyerges is the author of over 2 dozen books on survival and self-reliance, the founder of the School of Self-Reliance, and an educator since 1974. More information at www.SchoolofSelf-Reliance.com]

For several years, I have conducted a field class called Seasonal Foraging, which consists mostly of beginning students who want to know how to identify edible and useful plants. Each student is looking for a practical way to begin using some of nature’s abundant bounty in their own lives.

Educator Barbara Kolander collects wild Mediterranean mustard flowers.

I realize that I’ve been foraging most of my life, partly due to economic necessity but mostly because I’ve enjoyed the adventure of learning how hunt and forage peoples of the past survived.

I have always regarded the many traditional skills of self-reliance and bushcraft as worthy of mastery simply for the feeling of self-confidence that they impart. I find most of the television and on-line versions of “survival” a bit skewing, since the tv shows are so often about competition and making money. Not everyone shares my perspective, and that’s ok.

Home grown potatoes, from the Nightshade family.

SEASON

In my Seasonal Foraging class, I take students to the same (or very similar) location four times a year – near the solstices and equinoxes – to observe the seasonal changes, and to observe what is in season at the moment, and what will be available in the coming months.

One benefit of viewing our environment in this very positive and practical manner is that the students tend to become natural protectors of the environment. When you see every plant as useful, and valuable to your daily life, you want those environments to be maintained and protected. And you would never just uproot a plant if you only need to use its leaves, which I’ve seen “foragers” do all too often. It’s an act of self-interest to never uproot a plant that you don’t need to uproot.

Take lamb’s quarter for example. This is an annual, originally from Europe, which can today be found all over the world. The leaves can be eaten in dishes raw or cooked, and it’s one of the top most nutritious plants in the world. When I have it in my yard, I just pinch off the leaves I need. I never uproot it. In doing this over the past several decades, I’ve noted that the plants I cut back actually live longer! That’s right –my pruning prevents the plant from flowering and seeding in its normal time, and extends its life up to a few more months. That’s several more months where I can harvest and eat lambs’s quarter – a point that could make a significant difference in hard times.

It’s important to see the big picture and not just think about today. Look ahead. Think seasonally. And keep in mind that the quickest way to learn the art of ethnobotany is to see the plants in the field. Books are a distant second best. And once you recognize plants in the field, one of the best ways to accelerate your learning is to watch each of them throughout the year. Get to know the plants as they sprout, as they mature, as they produce flowers and fruit, and as they dry up and die. No book provides that full spectrum of images.

“Foraging Wild Edible Plants of North America” by Nyerges

FAMILIES

It’s important for the beginner to learn the individual plants. After awhile, you know some very well, and you start to look at what you don’t know. My main mentor emphasized the great value of learning about and understanding botanical Families.

My mentor, Dr. Enari, pointed out that the chemistry often flowed within families, and by knowing certain families, you have a great insight into all the members of that family.

So what exactly is a botanical Family? Through centuries of observation, naturalists have observed the characteristics of flowers, and they have carefully analyzed those flowers. There are many types of flowers. A complete flower has sepals, petals, stamens and pistils. Some flowers do not have all those parts, and so are called incomplete.

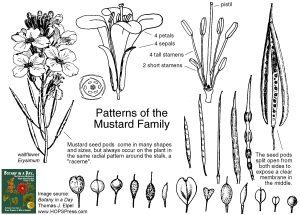

The Mustard Family flower pattern. Courtesy of Tom Elpel, from “Botany in a Day”

Despite the differences in leaf shapes and growing conditions, the flowers with identical parts (I’m simplifying) have traditionally been grouped into the same family. It’s a way to get a handle on nature, to see the patterns that exist and to find the order that seems to exist in nature. For example, any flower that has four sepals, four petals, four stamens (the male part) and one pistil (the female part) are classified in the Mustard Family. That family includes radishes, watercresss, wasabi, mustards, and broccoli – all of which appear very different, but whose flowers all consistently agree with that flower formula.

This order in nature helps the new botanist to identify plants by giving a device by which to study and classify. And in this case, since there are no poisonous member of this family, any plant you find with four sepals, four petals, six stamens, and one pistil can at least be tested for palatability since it will most likely be an acceptable food.

There are quite a few completely edible plant families. When I was first researching this with Dr. Enari, he identified perhaps three dozen such families that were entirely safe, and he always encouraged me to see the relationship of each plant within a family. It was not a “shortcut” he warned, but a way to always see a bigger picture, and a way to make great progress in botanizing.

Explorer Ben Hererra examines the lamb’s quarter plant.

SOME FAMILIES HAVE QUESTIONABLE MEMBERS

Knowing that a wild plant is related to a known edible plant does not make the wild plant edible, however. There are at least two botanical Families – the Nightshade and the Parsley Families – which contain many good edibles, and many that could also kill you.

Wild tobacco, which could cause sickness and death if eaten.

In my first book, “Guide to Wild Foods,” I included an appendix describing many of the entirely safe to eat plant families. I found that most people didn’t read it, but it was perhaps the most important part of the book. You can also get a similar insight by reading Tom Elpel’s excellent book, “Botany in a Day.” Both those books are available wherever quality books are sold, and they will accelerate your botanical education.

Photos by Christopher Nyerges unless otherwise indicated.

Cover photo: Christopher Nyerges collects watercresss. Photo by Barbara Kolander.